Abstract

Implementing the “deforestation-free” policy for trade in domestic and/or international products/commodities that enter the EU, UK, and USA has targeted palm oil. The policy is new protectionism carried out by palm oil competitor countries. The policy’s implementation can potentially sponsor more extensive deforestation and higher carbon emissions. Although the volume of palm oil trade in these three countries is only 17 percent of the volume of world palm oil imports, palm oil producers need to raise a memorandum of objection to this policy to protect the existence of palm oil and preserve the global environment.

Key Takeaways

- Implementing the “deforestation-free” in the EU, UK and USA will threaten palm oil with a share of 17 percent in the volume of world palm oil imports. Although palm oil producers can easily shift their palm oil exports to other countries, they need to raise a memorandum of objection to the policy.

- The “deforestation-free” policy continuation of a series of policies that impede palm oil trade in these countries/regions. This policy can move and enlarge global deforestation to other vegetable oil crops that are wasteful of deforestation both in the “deforestation-free” countries/regions or in other countries.

Introduction of Deforestation Free

Three countries/regions, the European Union (EU), the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States of America (USA), have issued and implemented a deforestation free policy. The EU have issued the Regulation on Deforestation-Free Commodity/Product in September 2022, which will into inforce 2023. Previously, the USA had also implemented the Fostering Overseas Rule of Law and Environmentally Sound Trade Act (FOREST Act) in 2021. The UK has also implemented deforestation free policy as stated in the UK Environment Act 2021, which takes effect since 2021. Although there are some differences among them, they have the same principle, namely “deforestation-free” for products/commodities traded both in the domestic and/or international market.

Some of the principles of the anti-deforestation policies of the EU, UK, and USA (UK Parliement, 2021; Weiss & Shin, 2021; Monard & Manistis, 2021; McCarty, 2022; Weiss et al., 2022; Chain Reaction Research, 2022) include: (1) the “deforestation-free” policy applies to illegal deforestation (USA, UK) and the EU covers legal, illegal, and forest degradation; (2) the commodities and products targeted by these policies are what they call forest risk commodities, both domestic and imported (for the EU and UK) and only imported for the USA; and (3) exporting countries of forest risk commodities are categorized into three groups based on the “deforestation-free” principle are low-risk, standard-risk, and high-risk with mandatory due diligence.

Although there are several commodities that are the target of the “deforestation-free” policy in these countries/regions, palm oil appears to be the main target of these policies. This can be traced to the background of this policy. For example, in the USA, it is reflected in the statement of Senator Schatz (one of the proponents of the policy) that “… half of the products in American grocery stores contain palm oil and most of that comes from illegally deforested land around the world…”.

Likewise, since the beginning of the policy drafting phase, palm oil has been the main driven deforestation (embodied deforestation) in the EU (European Commission, 2013). So, it is not surprising that the policy was designed to suppress the development of the global palm oil industry. Therefore, Indonesia, as the world’s largest palm oil producer, needs to mobilize diplomatic power to counter this policy.

This article will discuss how large palm oil imports are in the deforestation free countries/regions. This was followed by a discussion of these policies as a form of protectionist trade policy.

PALM OIL IMPORT IN “DEFORESTATION-FREE” COUNTRIES/REGIONS

The EU, the UK, and the USA are three of the main export destinations for global palm oil. In the consumption of vegetable oil in the EU (including the UK), palm oil occupies the second largest share, after rapeseed oil. Meanwhile, the structure of vegetable oil consumption in the USA shows that palm oil ranks third, after soybean oil and rapeseed oil.

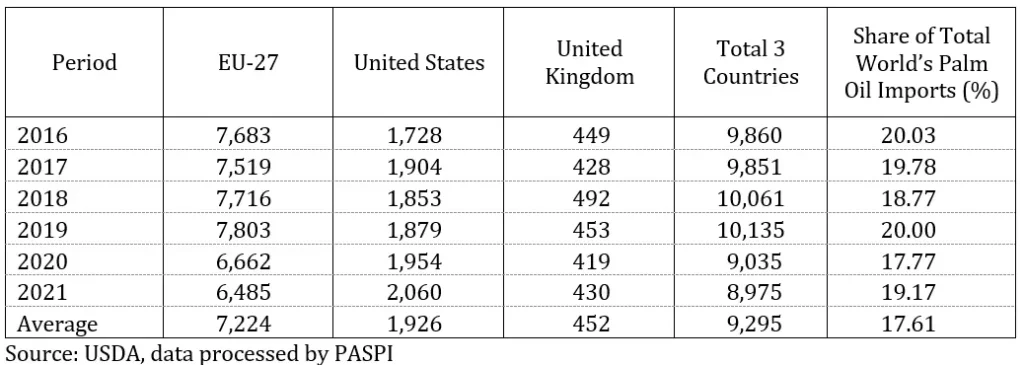

In 2016–2021 (Table 1), the EU’s import volume of palm oil averaged around 7.2 million tons per year. The volume of palm oil imports in 2016 was still approximately 7.6 million tons and increased to 7.9 million tons in 2019, but it continued to decline to 6.4 million tons in 2021.

So far, the use of palm oil in the EU has changed. Almost 80 percent of the palm oil imported by the EU in 2008 was used for food, feed, and toiletries. Meanwhile, only about 20 percent of palm oil is used for energy. Ten years later, the use of palm oil in the EU has changed drastically. In 2018, roughly 65 percent was used for energy, including biodiesel and power generation and the rest (35 percent) was used for food, feed, and toiletries (Transport and Environment, 2019).

The decline in EU import volumes since 2020 is related to the RED II policy, which gradually phase-outs palm oil for EU biofuels from 2020 to 2030. It is estimated that with RED II in 2030, EU palm oil import volumes will decrease to around 4 million tons (Fern, 2022; Chain Reaction Research, 2022).

In contrast to the EU, the average volume of USA palm oil imports is still around 1.9 million tons per year. The import volume increased from 1.7 million tons in 2016 to 2.1 million tons in 2021. Likewise, UK palm oil imports still tends to increase, from around 449 thousand tons to 490 thousand tons in the same period, or an average of about 452 thousand tons per year.

If we compare the total volume of world palm oil imports, the share of the countries/regionS implementing a “deforestation-free” policy is relatively small. The total volume of world palm oil imports is around 46.8 million tons to 53.6 million tons or an average of 52.8 million tons per year. The volume of palm oil imports share for three countries/regions is only about 17.6 percent.

Thus, implementation the “deforestation-free” policy in the three countries/regions is not very significant in affecting the global palm oil market. This means that if the “deforestation-free” policy is applied to all imported palm oil, it will not be too difficult for the world’s palm oil-producing countries to shift it to countries that do not demand “deforestation-free”.

However, palm oil-producing countries need to protest against this policy. Apart from not being the best solution to tackle global deforestation, if the world’s palm oil producers do not raise an objection/protest, the “deforestation-free” policy can spread to other countries/regions and damage the image of palm oil.

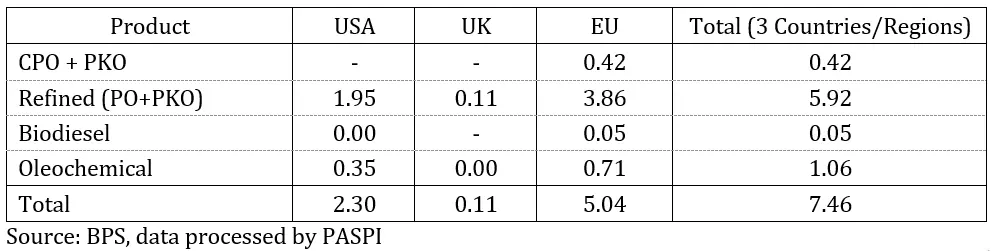

Indonesia as the world’s largest producer and exporter of palm oil, also exports palm oil and its derivatives to these three countries/regions (Table 2).

The value of Indonesian palm oil exports to the “deforestation-free” countries/regions in 2021 will reach around USD 7.4 billion. The export value was obtained from exports to the EU amounted to USD 5 billion, exports to the UK amounted to USD 0.11 billion, and exports to the USA amounted to USD 2.3 billion. With the total value of Indonesian palm oil exports in 2021 reaching around USD 36.2 billion (PASPI Monitor, 2022), it means that the contribution of Indonesia’s palm oil exports from the “deforestation-free” countries/regions only reaches about 20 percent.

NEW STYLE PROTECTIONISM

Policies that hampering palm oil in the UK (including the UK) market are not something new. In the last 20 years, the EU has diligently made policies that impede the palm oil trade. First, the Palm Oil Free Campaign, which started in 2006, requires the food, beverage, and pet food industries not to use palm oil as a raw material. This movement is not an official policy of European governments and even contradicts the EU regulations on food labeling and advertising (Regulation No 1169/2011, Directive 2000/13/EC, Directive 2006/114/EC, and Directive 2005/29/EC). But the EU government also did not provide a ban on the movement.

Second, France applies progressive and regressive palm oil import tariffs. At first, France imposed a levy on imports of palm oil of 300 euros in 2017, then increased to 500 euros in 2018. The French government again levied an even larger levy of 700 euros in 2019 and 900 euros in 2020 for every tonne of palm oil imported to the country. In addition, if palm oil is used for food, it is subject to an additional ad valorem. The levy is enforced as an environmental tax (Pigouvian Tax), which is a form of internalizing the negative externalities of the palm oil production and consumption process. The France government did not enforce under pressure from palm oil producers.

Third, the EU has implemented an Anti-Dumping Import Duty (BMAD) policy for palm biodiesel in the country of around 8.8-23.3 percent since 2013. The European Union has also sued Indonesia’s palm biodiesel in the WTO on charges of dumping and subsidies. Indonesia won the accusation of dumping/subsidy on their palm oil biodiesel in the EU’s Court and WTO.

Fourth, palm oil exports to Europe (EU) face the threat of an embargo/resolution issued by the European Parliament in early April 2017. The palm oil embargo is linked to environmental issues, including embodied deforestation, forest fires, greenhouse gas emissions, and peat (European Commission, 2013). They also plan to phase out palm oil as biodiesel feedstock starting in 2021 (RED-I). However, with intensive lobbying from the Indonesian and Malaysian governments, they have succeeded in loosening the policy (RED II), which only applies to biofuels and its implementation has been pushed back to 2030, while the use of food palm oil and others does not apply.

Not only in the European Union, but also in the United States, where the American Soybean Association (ASA) has been at the forefront of anti-tropical oil campaigns/movements since the early 1980s. At that time, the ASA accused palm oil of containing cholesterol causing cardiovascular. They also submitted a resolution to the US Congress to ban palm oil imported to the US. However, the evidence made by experts submitted by tropical oil, mainly Indonesian and Malaysian experts, has proven the accusations wrong.

Then, the accusations of dumping issues on Indonesian palm oil biodiesel subsidies were also supported by the ASA. The position statement entitled “Countervailing Duties on Biodiesel Imports”, published on August 24, 2017, revealed that the ASA assessed that palm oil biodiesel imported from Indonesia and Argentina was subsidized so that it supported the implementation of Anti-Dumping (BMAD).

Following the EU’s efforts, the US government, through the United States Department of Commerce (USDOC), implemented an anti-dumping policy on palm oil biodiesel on March 23, 2017. The reason for implementing this policy is that the US government considers Indonesian palm biodiesel to be subsidized. Furthermore, at the end of August 2017, USDOC plans to implement Anti-Dumping Import Duties on Indonesian palm oil biodiesel with tariffs ranging from 34.5 to 64.73 percent.

The accusations were actually fabricated, which were used to cover up the soybean oil protective policy carried out by the US government. Various studies (GIS-IISD, 2007; PASPI, 2018) show that soybean biodiesel in the American market has enjoyed subsidies of up to 63 percent, so accusations against palm oil biodiesel are only diversionary issues.

Implementing the “deforestation-free” policy in the EU, UK, and USA seems to be just a continuation of the protectionist practices that have been carried out so far. If the goal is to stop global deforestation, these policies are ineffective because the volume of palm oil that targets these policies is only about 17 percent of the global palm oil import volume. On the other hand, global palm oil producers may divert palm oil from the regions to other countries (Chain Reaction Research, 2022).

The presence of palm oil in the European and US markets is a solution to the food fuel trade-off that has the potential to occur in these countries/regions. Palm oil’s much higher productivity (which has the potential to be improved) combined with a lower price compared to soybean oil, rapeseed oil, and sunflower seed oil can prevent them from trade-off in the use of vegetable oils for food or energy.

If the USA, UK, and the EU want to contribute to preventing global deforestation, they must shift their supply of vegetable oil from soybean oil, rapeseed oil, and sunflower seed oil, which are relatively more deforestation and emitting emissions, to palm oil which save deforestation (PASPI Monitor, 2021ab) and emissions (Beyer et al., 2020; Beyer and Rademacher, 2022; PASPI Monitor, 2021c).

Implementing the “deforestation-free” policy in the USA, UK, and EU to phase out palm oil cause greater deforestation in other countries/regions through the production of other vegetable oil crops. On the other hand, shifting the consumption of vegetable oils from deforestation-intensive vegetable oils to deforestation-saving vegetable oils is a wise and effective way to reduce the deforestation rate.

Conclusion

Implementing the “deforestation-free” in the EU, UK and USA will threaten palm oil with a share of 17 percent in the volume of world palm oil imports. Although palm oil producers can easily shift their palm oil exports to other countries, they need to raise a memorandum of objection to the policy.

The “deforestation-free” policy continuation of a series of policies that impede palm oil trade in these countries/regions. This policy can move and enlarge global deforestation to other vegetable oil crops that are wasteful of deforestation both in the “deforestation-free” countries/regions or in other countries.

References

- Beyer RM, AP Durán, TT Rademacher, P Martin, C Tayleur, SE Brooks, D Coomes, PF Donald, FJ Sanderson. 2020. The Environmental Impacts Of Palm Oil And Its Alternatives.

- Beyer R, Rademacher T. 2021. Species Richness and Carbon Footprints of Vegetable Oils: Can High Yields Outweigh Palm Oil’s Environmental Impact?. Sustainability. 13: 1813.

- Chain Reaction Research. 2022. EU Deforestation Regulation: Implications for Palm Oil Industry and Its Financers. [internet].

- European Commission. 2013. The Impact of EU Consumption on Deforestation: Comprehensive Analysis of the Impact of EU Consumption on Deforestation.

- Fern. 2022. Palm Oil Production, Consumption and Trade Patterns: The Outlook From An Eu Perspective.

- McCarty J. 2022. What Is the FOREST Act? Everything to Know About the US Bill to Fight Deforestation. [internet].

- Monard E, B Manistis. 2021.The European Commission’s Proposed Ban on Products Driving Deforestation and Forest Degradation.

- PASPI Monitor. 2021a. Palm Oil Free is Driving the Global Deforestation. Palm Oil Journal Analysis of Palm Oil Strategic Issues. 2(14):357-361.

- PASPI Monitor. 2021b. Palm Oil Industry Saves Global Deforestation?. Palm Oil Journal Analysis of Palm Oil Strategic Issues. 2(18): 383-390.

- PASPI Monitor. 2021c. Carbon Emissions in Oil Palm Plantation Versus Other Vegetable Oil Plantations. Palm Oil Journal Analysis of Palm Oil Strategic Issues. 2(46): 570-574.

- PASPI Monitor. 2022. The Indonesian Foreign Exchange And Trade Balance In 2021 Hit A Record High. Journal Analysis of Palm Oil Strategic Issues. 3(2): 589-593.

- UK Parliement. 2021.Environment Act 2021: Government Bill

- USDA. 2022. Oilseeds: World Market and Trade

- Weiss J, K Shin. 2021. Potential Implications of the FOREST Act of 2021 and Related Developments in Other Jurisdictions.

- Weiss J, K Shin, E Monard, S Tilling 2022. Comparing Recent Deforestation Measures of the United States, European Union, and United Kingdom. [internet].

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

What are the anti-deforestation policies of the EU, UK, and USA?

The EU, UK, and USA have all implemented anti-deforestation policies that aim to make products and commodities traded in the domestic and international market “deforestation-free.” The EU’s policy covers illegal, legal, and forest degradation, while the UK and USA’s policies only cover illegal deforestation. The policies target forest risk commodities, both domestic and imported for the EU and UK, and only imported for the USA. Exporting countries of forest risk commodities are categorized into three groups based on the “deforestation-free” principle: low-risk, standard-risk, and high-risk with mandatory due diligence.

What is the main target of these anti-deforestation policies?

The main target of these anti-deforestation policies is palm oil, as it has been the main driver of deforestation in the EU and the USA. This is due to the fact that a large portion of palm oil used in American grocery stores comes from illegally deforested land around the world, and palm oil has been a main driver of deforestation in the EU since the policy drafting phase.

How much palm oil does the EU import?

In 2016-2021, the EU’s import volume of palm oil averaged around 7.2 million tons per year. The volume of palm oil imports in 2016 was still approximately 7.6 million tons and increased to 7.9 million tons in 2019, but it continued to decline to 6.4 million tons in 2021.

How is the use of palm oil in the EU different now compared to 10 years ago?

The use of palm oil in the EU has changed drastically in the past 10 years. In 2008, almost 80 percent of the palm oil imported by the EU was used for food, feed, and toiletries. Meanwhile, only about 20 percent of palm oil is used for energy. However, in 2018, roughly 65 percent was used for energy, including biodiesel, and only 35 percent was used for food, feed, and toiletries.

How do the anti-deforestation policies of the EU, UK, and USA affect Indonesia as the world’s largest palm oil producer?

The anti-deforestation policies of the EU, UK, and USA are likely to negatively impact Indonesia as the world’s largest palm oil producer. These policies are designed to suppress the development of the global palm oil industry, and as such, Indonesia may need to mobilize diplomatic power to counter this policy.

How will these policies affect the palm oil industry as a whole?

These policies are likely to have a significant impact on the global palm oil industry, as they target a major market for palm oil exports and may lead to decreased demand for palm oil products. This could result in a decrease in production and potential negative economic impacts for countries heavily dependent on palm oil exports. Additionally, companies in the palm oil industry may need to invest in new sustainability practices and certifications in order to comply with these policies.

How do these policies ensure that the commodities and products traded in these countries/regions are deforestation-free?

These policies aim to ensure that commodities and products traded in these countries/regions are deforestation-free by placing restrictions on the import and use of products from high-risk exporting countries. Exporting countries are categorized into three groups: low-risk, standard-risk, and high-risk. Due diligence is mandatory for high-risk countries and companies need to prove that their product is not linked to deforestation. This will be done through a certification process, traceability, and an independent verifier.

How will these policies affect the price of palm oil and other forest risk commodities?

These policies may lead to an increase in the price of palm oil and other forest risk commodities, as companies may need to invest in new sustainability practices and certifications in order to comply with these policies. Additionally, the decreased demand for palm oil products could also lead to an increase in price. However, it is also possible that the price may not change significantly as these policies may lead to a shift in demand towards other vegetable oils.

Will these policies have any impact on the deforestation in countries outside of the EU, UK and USA?

These policies may have some impact on deforestation in countries outside of the EU, UK and USA, as they may lead to a decrease in demand for products linked to deforestation. However, it is important to note that these policies only target imports to these countries/regions, so their impact on deforestation in other countries may be limited.

Are there any alternatives to palm oil that can be used in these countries/regions?

There are several alternatives to palm oil that can be used in these countries/regions, such as soybean oil, rapeseed oil, sunflower oil, and coconut oil. However, it’s important to note that these alternatives may also have their own environmental impact and should be evaluated before being considered as replacement. Additionally, palm oil is a versatile oil that can be used in many products and it’s hard to find a direct replacement for it.